Dynamic Time Warping vs Lock-Step

Source:vignettes/articles/dynamic_time_warping_and_lock_step.Rmd

dynamic_time_warping_and_lock_step.RmdSummary

The R package distantia provides tools for comparing

time series through two distinct methods: dynamic time warping (DTW) and

lock-step (LS). These approaches cater to different analysis needs: DTW

for handling temporal shifts and LS for preserving temporal alignment.

This article explores the conceptual foundations of both methods, their

implementation in distantia, and showcases their practical

use with code examples.

Setup

The packages required to run the code in this article are

distantia and dtw. The latter is not a

dependency of distantia, but will help put into context key

details of how DTW works.

Example data

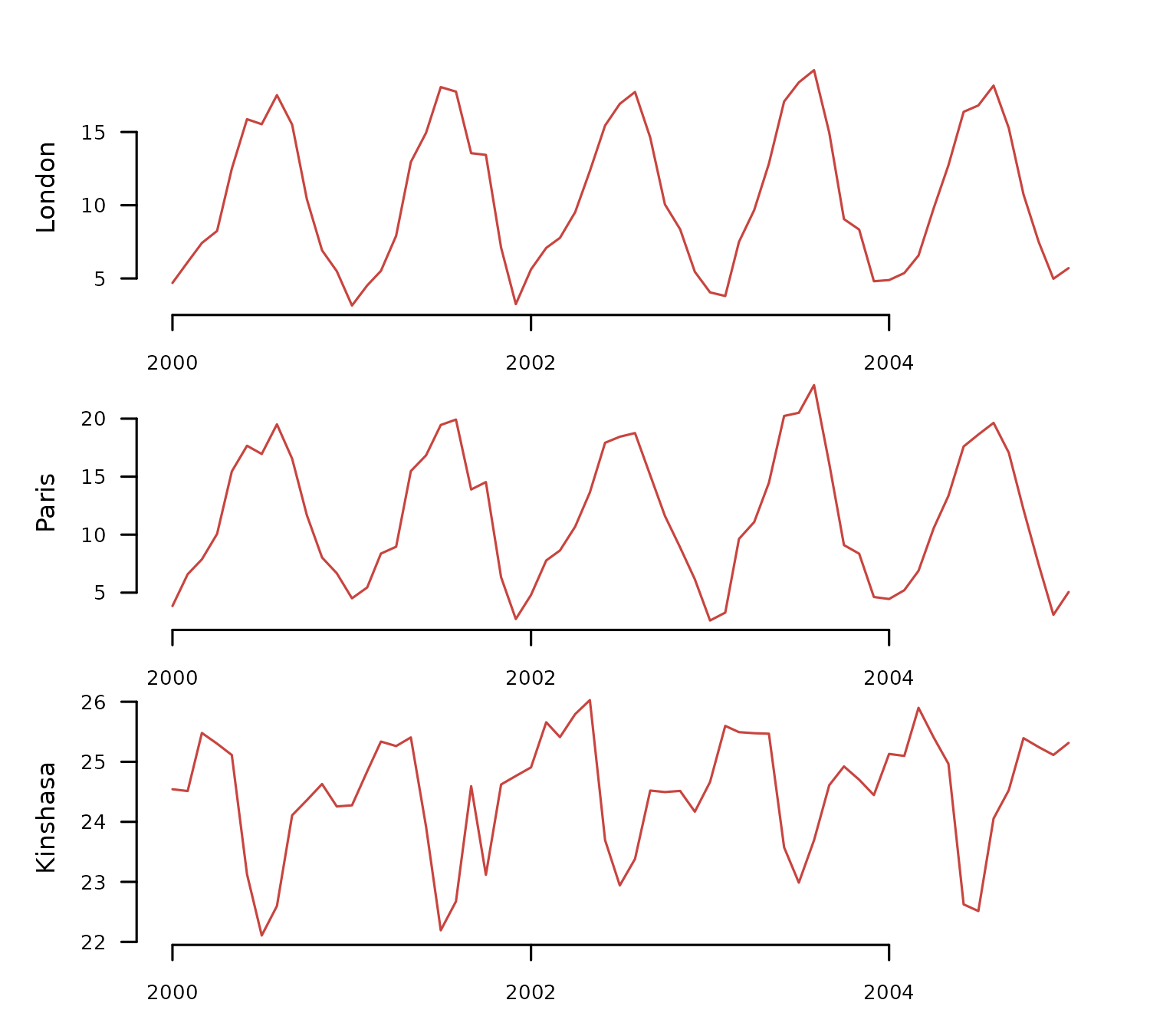

The cities_temperature dataset contains monthly

temperature records for 20 cities. The code below transforms it into a

Time Series List (TSL) and selects a subset of three cities with

temperature time series from 2000 to 2005.

tsl_raw <- distantia::tsl_initialize(

x = cities_temperature,

name_column = "name",

time_column = "time"

) |>

distantia::tsl_subset(

names = c("London", "Paris", "Kinshasa"),

time = c("2000-01-01", "2005-01-01")

)

distantia::tsl_plot(

tsl = tsl_raw,

ylim = "relative",

guide = FALSE

)

The transformed TSL contains two synchronous time series in the Northern Hemisphere with similar temperature ranges (London and Paris) and one in the Southern Hemisphere (Kinshasa) with a higher average and a shifted temporal pattern.

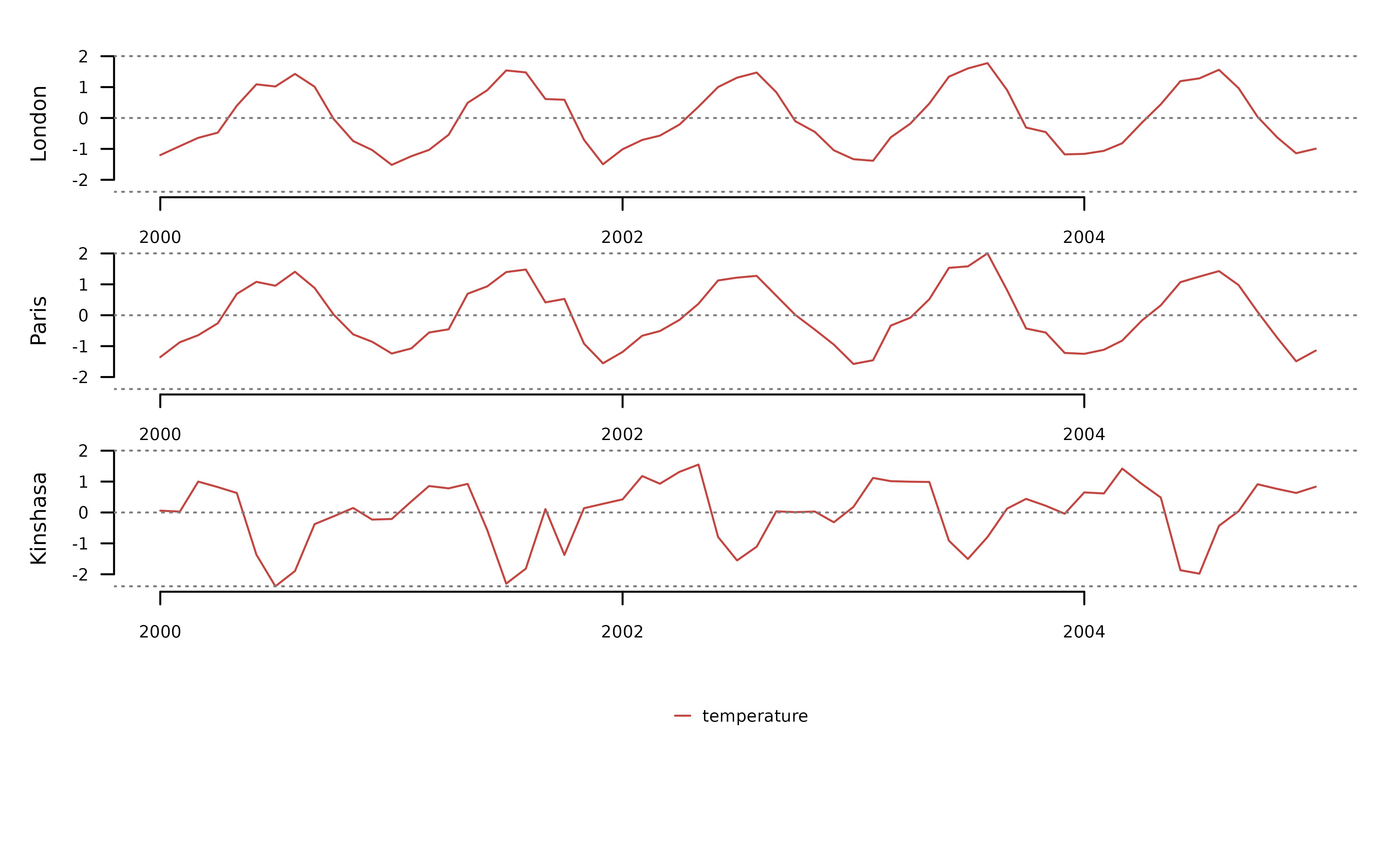

To facilitate the comparison of DTW and LS, the code below applies

the functions tsl_transform() with

f_detrend_linear to remove any long-term trends in the

data, and with f_scale to scale and center each time series

separately.

tsl_scaled <- tsl_raw |>

distantia::tsl_transform(

f = distantia::f_detrend_linear

) |>

distantia::tsl_transform(

f = distantia::f_scale_local

)

distantia::tsl_plot(

tsl = tsl_scaled,

ylim = "relative",

guide = FALSE

)

Lock-Step (LS)

Lock-step methods compare values at corresponding time points, requiring time series of the same length sampled at identical times. This approach is well-suited for cases where maintaining the temporal alignment of the compared time series is crucial. The method is straightforward and computationally efficient.

In distantia, lock-step comparisons are carried out in

three steps:

1.- Sum the distances between pairs of samples observed at the same times.

2.- Sum the distances between consecutive samples within each time series.

3.- Compute the normalized dissimilarity score psi.

Let’s look first at a native R implementation of this idea using euclidean distances to keep it simple.

#extracting the data to shorten variable names

x <- tsl_scaled$London

y <- tsl_scaled$Kinshasa

#1.- sum of distances between pairs of samples

step_1 <- sum(sqrt((x - y)^2))

#2.- sum of distances between consecutive samples

step_2 <- sum(

sqrt(diff(x)^2) + sqrt(diff(y)^2)

)

#3.- compute normalized dissimilarity score

((2 * step_1) / step_2)

#> [1] 2.791279The function distantia() performs the same task when

lock_step = TRUE (default is FALSE).

df <- distantia::distantia(

tsl = tsl_scaled[c("London", "Kinshasa")],

lock_step = TRUE,

distance = "euclidean"

)

df$psi

#> [1] 2.791279The same can be done with the function distantia_ls(), a

simplified version of distantia() for lock-step

analysis.

df <- distantia::distantia_ls(

tsl = tsl_scaled[c("London", "Kinshasa")]

)

df$psi

#> [1] 2.791279Both functions can compute lock-step dissimilarity scores for all

time series in the argument tsl at once.

df <- distantia::distantia_ls(

tsl = tsl_scaled

)

df[, c("x", "y", "psi")]

#> x y psi

#> 1 London Paris 0.2298458

#> 3 Paris Kinshasa 2.7046009

#> 2 London Kinshasa 2.7912785As expected, London and Paris show the most similar temperature time series, while London and Kinshasa are the most different ones.

Dynamic Time Warping

Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) warps the time axes of two time series to maximize pattern similarity, even when temporal shifts are present. This makes DTW ideal for comparing time series with similar shapes but misaligned time points. However, it is computationally more intensive and less efficient than the lock-step method, particularly for large datasets.

DTW involves three conceptual steps, similar to the lock-step method, but with additional complexity in the first step:

1.- Sum the distances between pairs of samples.

1a Compute a distance matrix between all pairs of samples.

1b Build the least-cost matrix.

1c Find the least-cost path.

1d Sum distances along the least-cost path.

2.- Sum distances between consecutive samples within each time series.

3.- Calculate the normalized dissimilarity score psi (with a slightly different formula!).

Now, let’s dive into the code.

The objective of the step 1 is computing the sum of distances between pairs of samples matched together by the time warping algorithm.

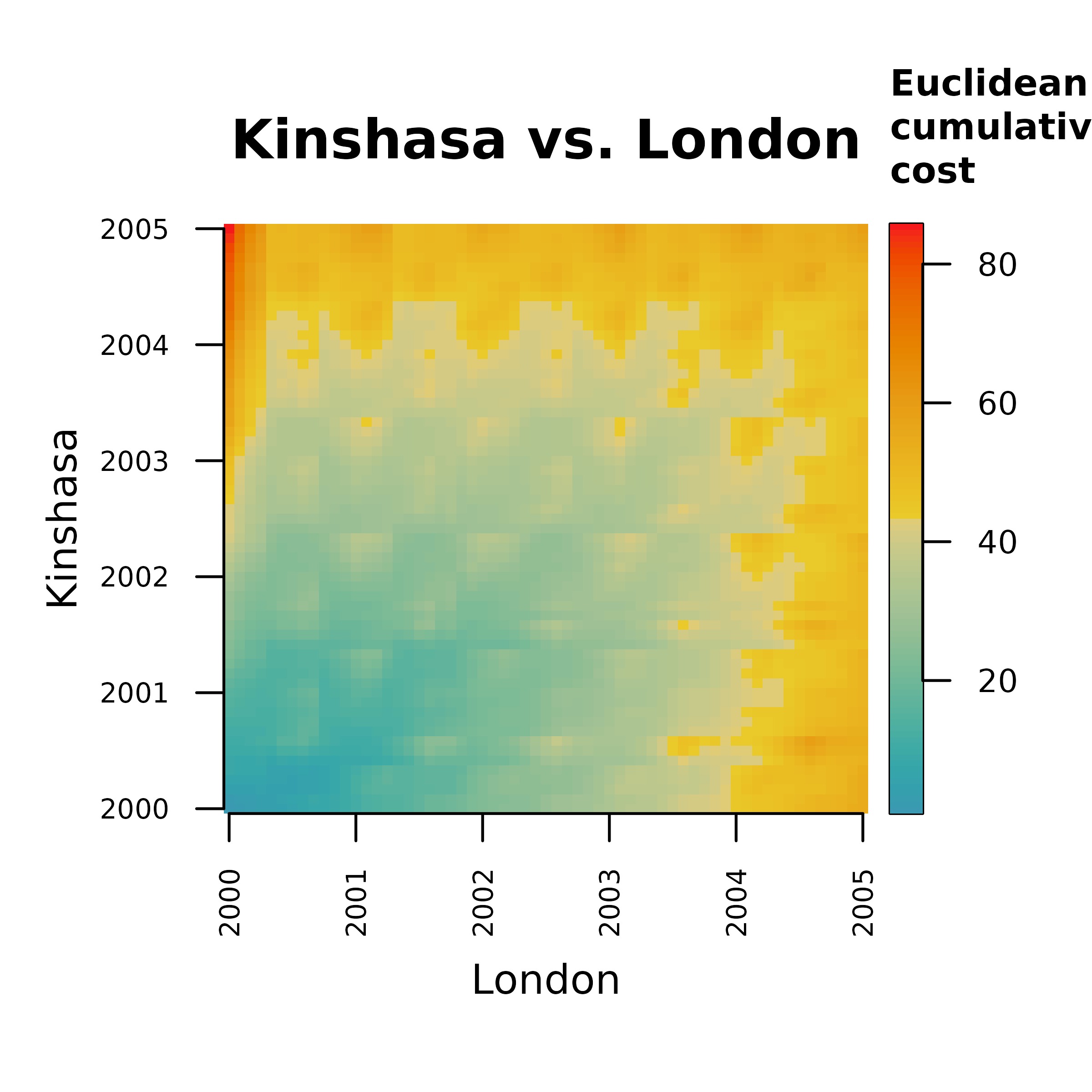

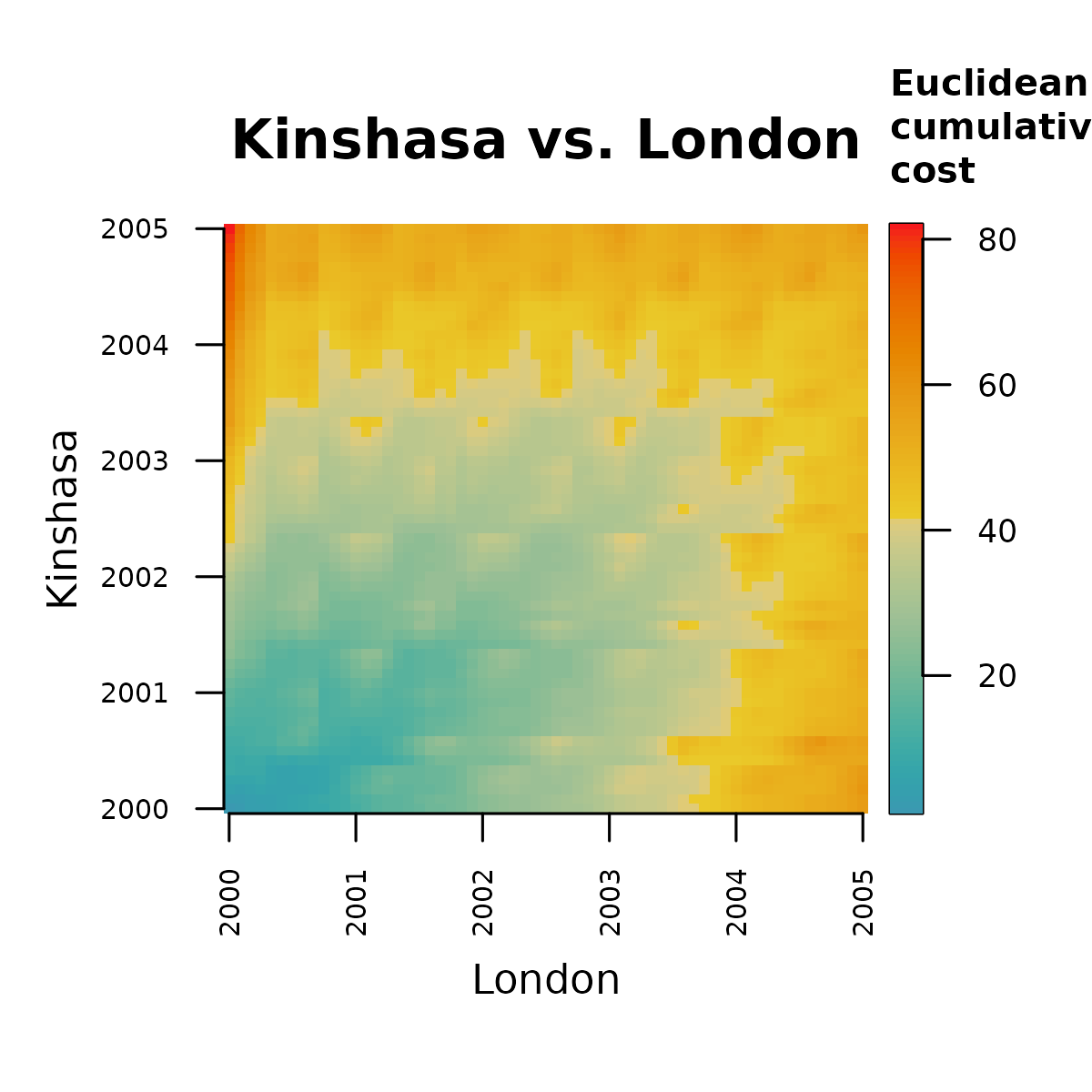

Step 1a computes the distance matrix between all

pairs of samples in both time series. Notice that all functions to

demonstrate the computation of the normalized dissimilarity score

psi follow the naming convention psi...().

m.dist <- distantia::psi_distance_matrix(

x = x,

y = y,

distance = "euclidean"

)

distantia::utils_matrix_plot(

m = m.dist,

diagonal_width = 0

)

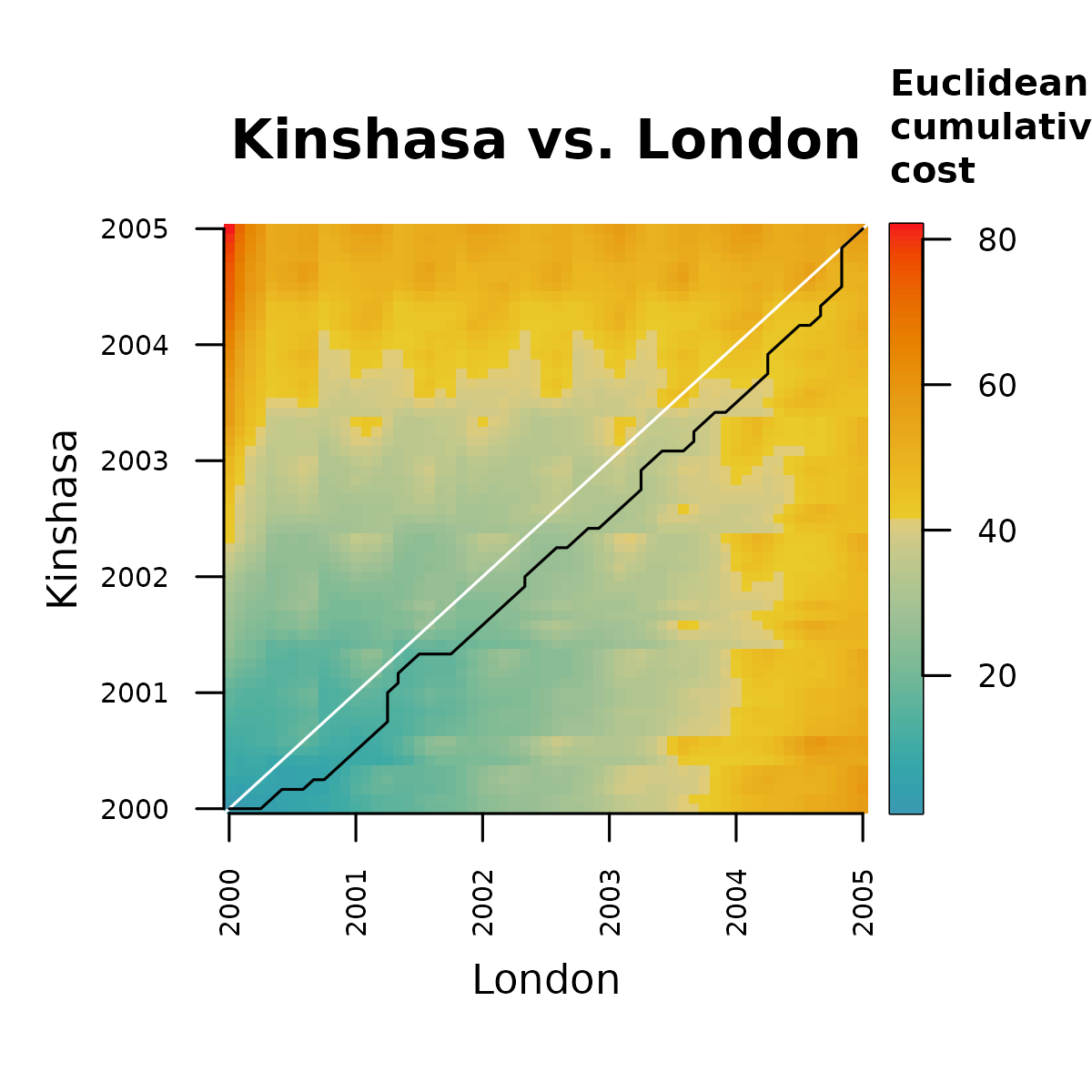

Step 1b involves transforming the distance matrix

into a cost matrix. This transformation requires a dynamic algorithm in

which each new cell adds its own distance to the distance accumulated by

its preceding neighbor. There are two implementations of this method in

distantia:

- orthogonal only: distance cost is only computed on the x and y axis, ignoring diagonals.

-

orthogonal and diagonal: distance cost is also

computed in diagonals, which are weighted by a factor of

1.414214 (square root of 2).

These options are wrapped in the function

psi_cost_matrix(), which by default, like

distantia() uses weighted diagonals.

m.cost <- distantia::psi_cost_matrix(

dist_matrix = m.dist,

diagonal = TRUE #default

)

distantia::utils_matrix_plot(

m = m.cost,

diagonal_width = 0

)

In step 1c, the distance and cost matrices are used to find the least-cost path.

m.cost.path <- distantia::psi_cost_path(

dist_matrix = m.dist,

cost_matrix = m.cost,

diagonal = TRUE #default

)

tail(m.cost.path)

#> x y dist cost

#> 76 6 3 0.09082845 4.579160

#> 77 5 2 0.19227643 4.450709

#> 78 4 1 0.71503492 4.178789

#> 79 3 1 0.88127572 3.463754

#> 80 2 1 1.14678108 2.582479

#> 81 1 1 1.43569743 1.435697Notice that the cost path data frame is ordered from bottom to top. The columns “x” and “y” represent sample indices of the time series London and Kinshasa. The figure below shows the least cost path on top of the cost matrix.

distantia::utils_matrix_plot(

m = m.cost,

path = m.cost.path

)

The step 1d finalizes the DTW logic by adding the

distances between pair of samples connected by the least-cost path. This

step is just sum(m.cost.path$dist), but it is implemented

in psi_cost_path_sum(), which also checks that the least

cost data frame is correct.

step_1 <- distantia::psi_cost_path_sum(

path = m.cost.path

)

step_1

#> [1] 36.18196Step 2 returns the distances between consecutive

samples within each time series, as computed by

psi_auto_sum().

step_2 <- distantia::psi_auto_sum(

x = x,

y = y,

distance = "euclidean"

)

step_2Finally, the step 3 computes the normalized dissimilarity score.

distantia::psi_equation(

a = step_1,

b = step_2,

diagonal = TRUE

)All these individual steps can be performed at once with the function

distantia() by setting the argument lock_step

to FALSE, or with the function

distantia_dtw().

df <- distantia::distantia(

tsl = tsl_scaled[c("London", "Kinshasa")],

lock_step = FALSE,

distance = "euclidean"

)

df[, c("x", "y", "psi")]

#> x y psi

#> 1 London Kinshasa 1.051902

df <- distantia::distantia_dtw(

tsl = tsl_scaled[c("London", "Kinshasa")]

)

df[, c("x", "y", "psi")]

#> x y psi

#> 1 London Kinshasa 1.051902As before, both functions can compute dynamic time warping

dissimilarity for all time series in the argument tsl at

once.

df <- distantia::distantia_dtw(

tsl = tsl_scaled

)

df[, c("x", "y", "psi")]

#> x y psi

#> 1 London Paris 0.2177902

#> 2 London Kinshasa 1.0519019

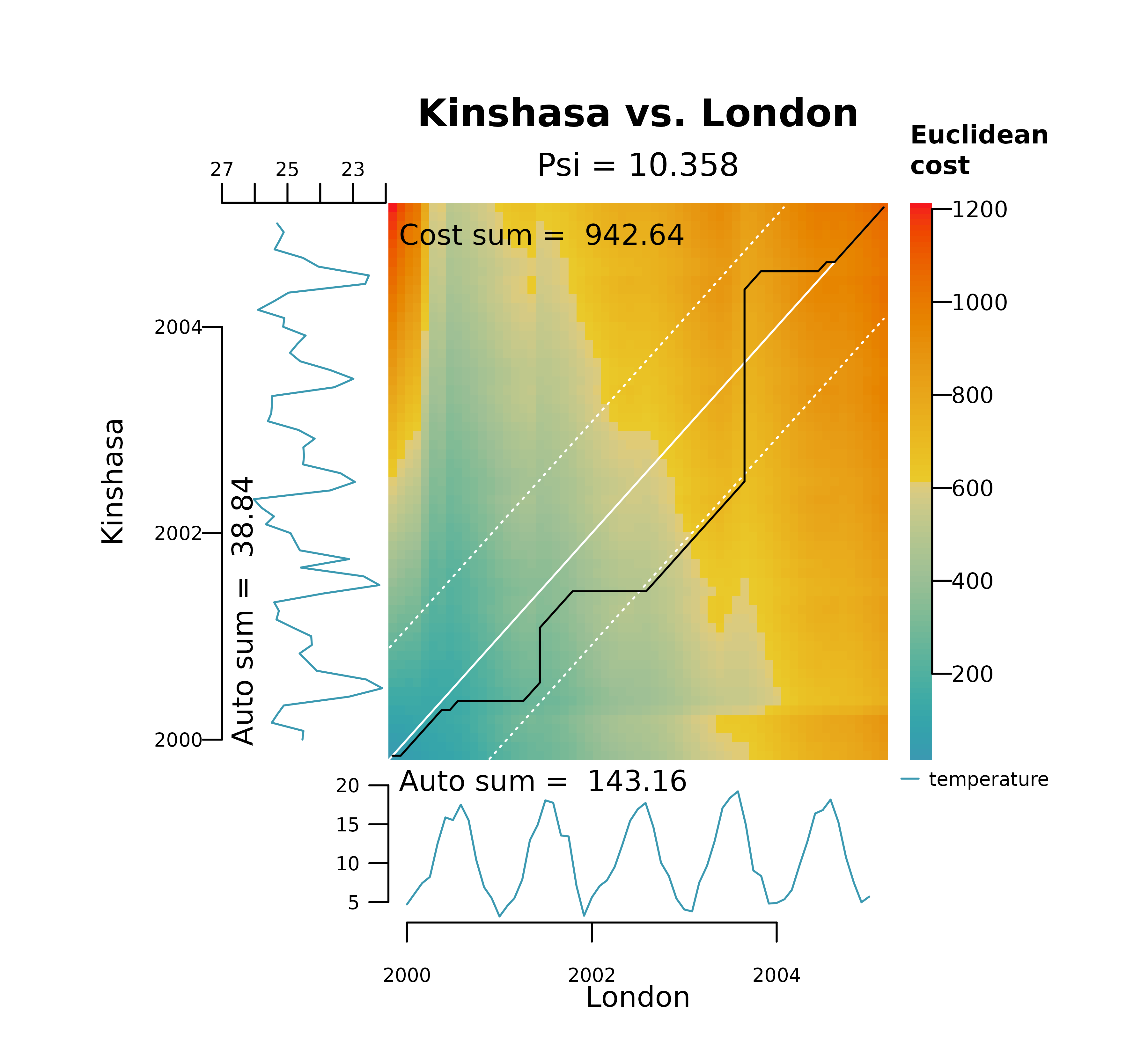

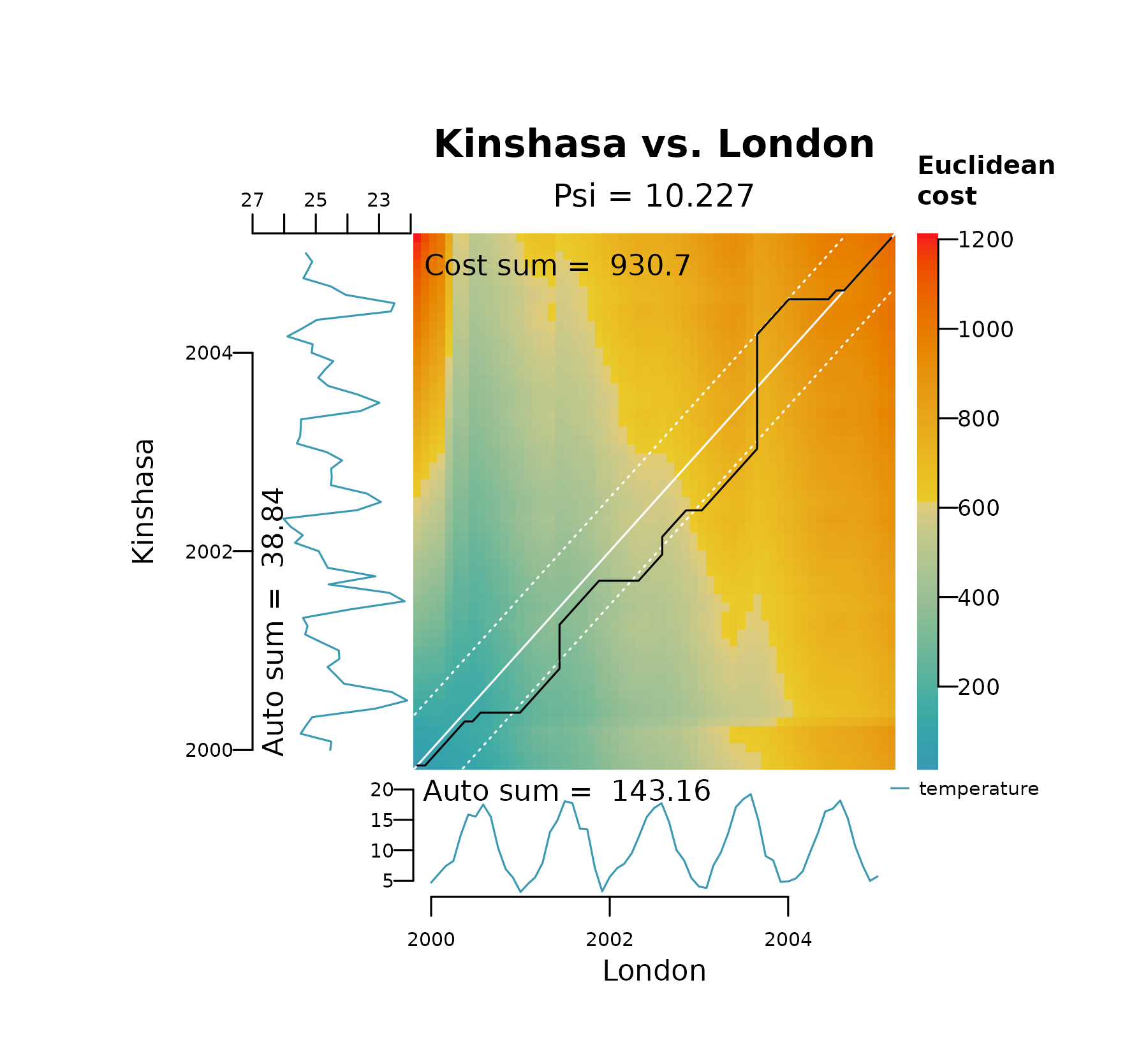

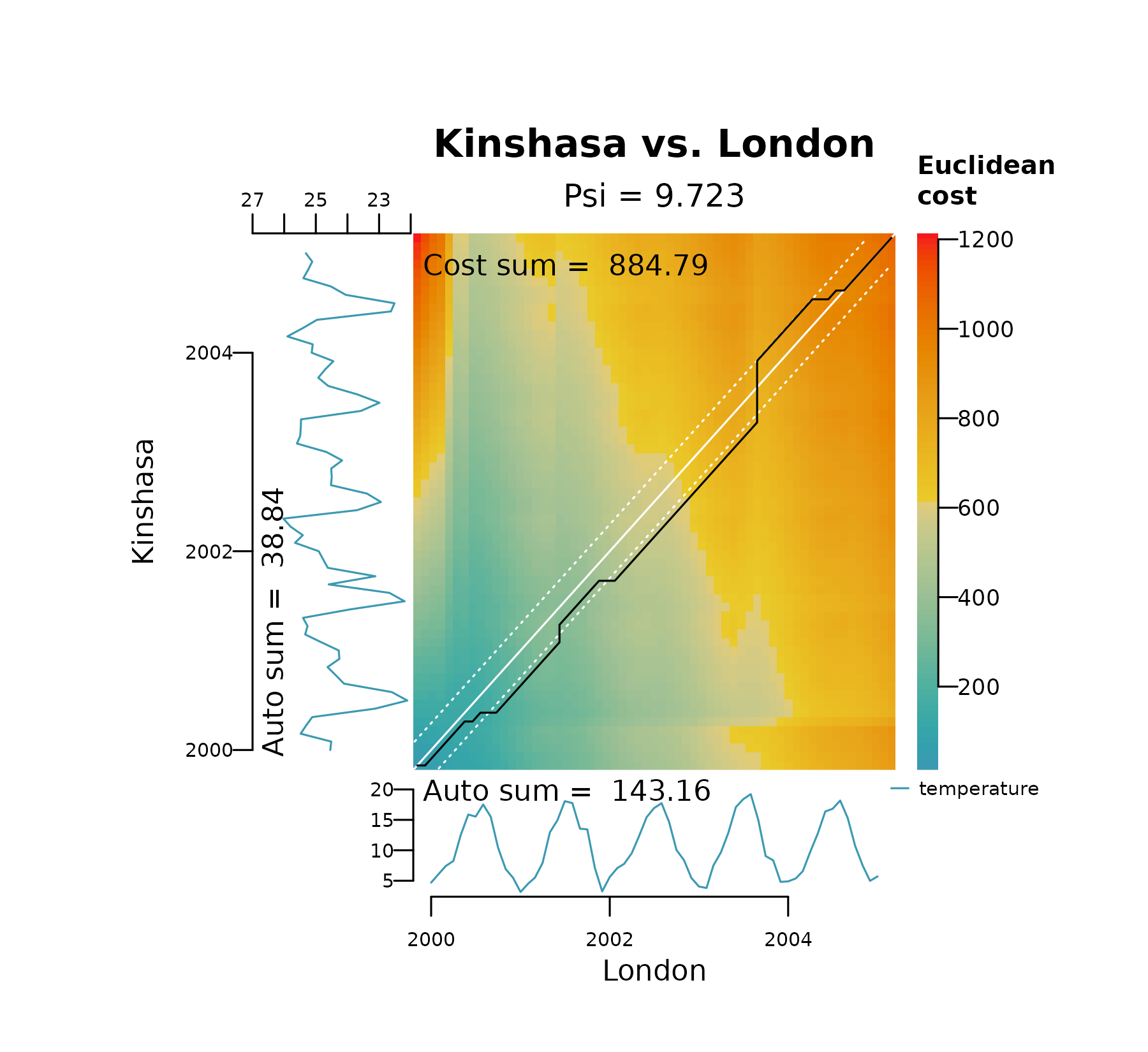

#> 3 Paris Kinshasa 1.1054414The function distantia_dtw_plot() offers a good

graphical representation of the warping result and decomposes the

computation of the psi dissimilarity score.

distantia_dtw_plot(

tsl = tsl_scaled[c("London", "Kinshasa")]

)

Pitfalls

DTW is an ideal method to compare time series with temporal shifts, and is applicable to regular and irregular time series with the same or different numbers of samples.

However, DTW is highly sensitive to differences in data magnitudes. As result, data that is not properly scaled may distort the warping, leading to .

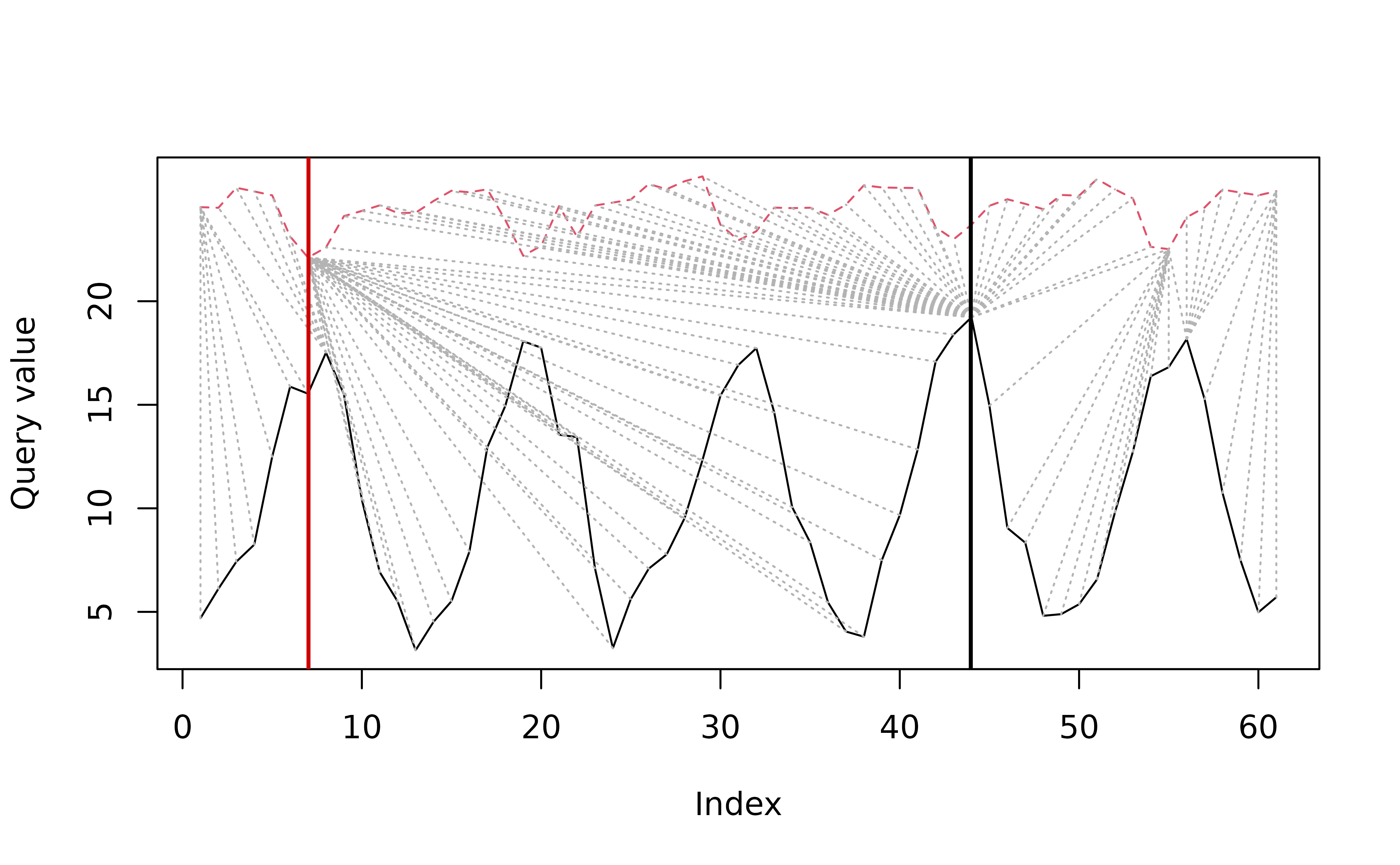

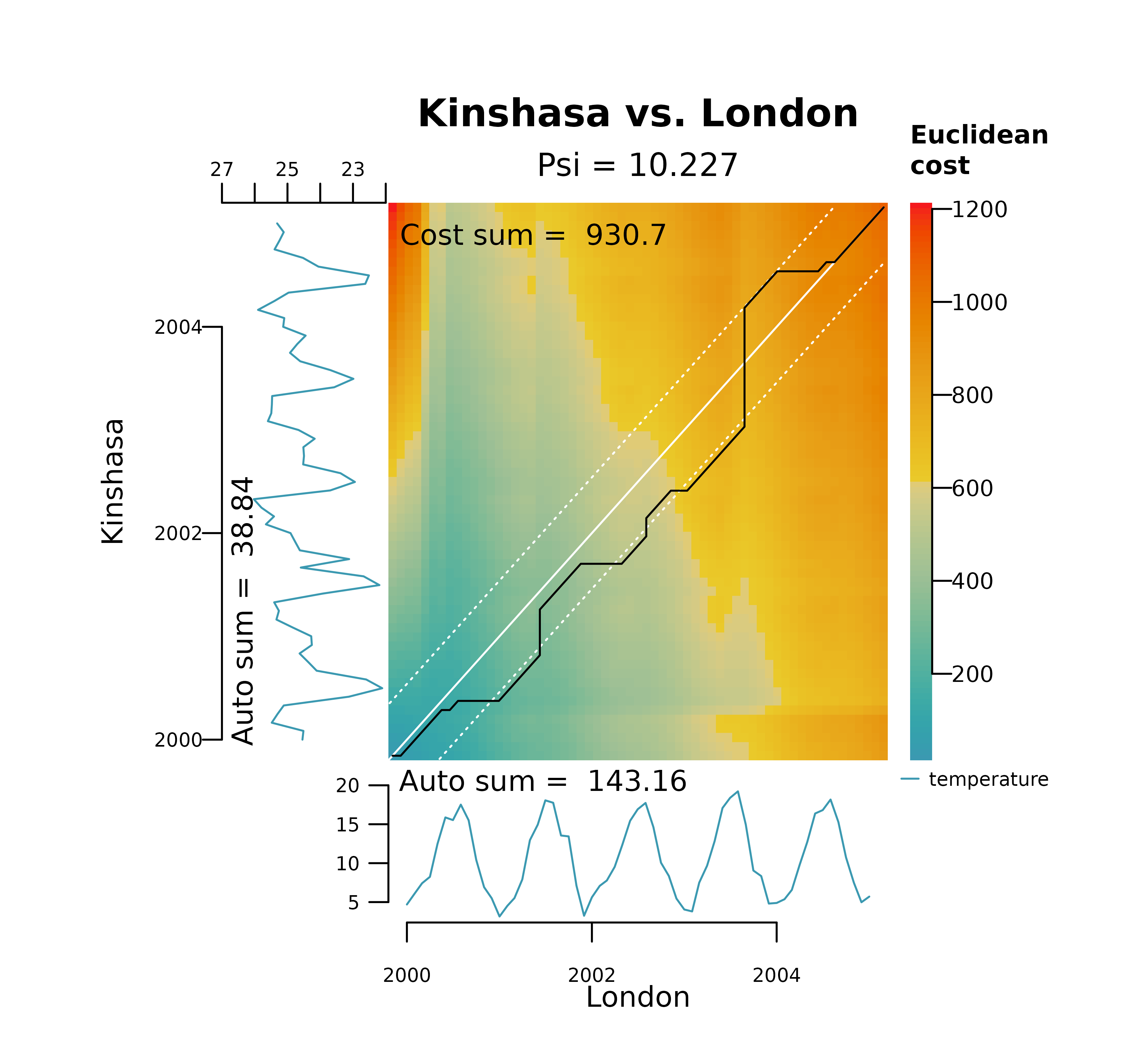

The plot below represents the DTW alignment of London and Kinshasa on the raw temperature data. It shows how DTW gets stuck in two local optima, one in the y axis (long horizontal line) at the minimum temperature in Kinshasa (winter of 2001), and another in the x axis (long vertical line) at the maximum temperature in London (summer of 2003). It also shows a distinctively large dissimilarity score.

distantia_dtw_plot(

tsl = tsl_raw[c("London", "Kinshasa")]

)

These long horizontal and vertical lines shown above provide an immediate diagnostic of a pathological warping, which happens when a relatively short segment of one time series maps to a much longer segment of another.

This is not a particular issue of the DTW algorithm implemented in

distantia, but a general behavior of time warping methods.

The code below shows a similar analysis performed with the R package dtw. The

default implementation ignores diagonals when building the cost

matrix.

xy_dtw <- dtw::dtw(

x = tsl_raw$London$temperature,

y = tsl_raw$Kinshasa$temperature,

keep = TRUE

)

plot(xy_dtw, type = "threeway")

The “twoway” plot provided by dtw shows the alingment as

a line bar, with the sample matches represented as dotted lines, and two

vertical lines highlighting the local optima

plot(xy_dtw, type = "twoway")

abline(v=0.13, col="red3", lwd = 2)

abline(v=0.70, col="black", lwd = 2)

There are two strategies that can be combined to control this issue: data scaling, and constrained DTW.

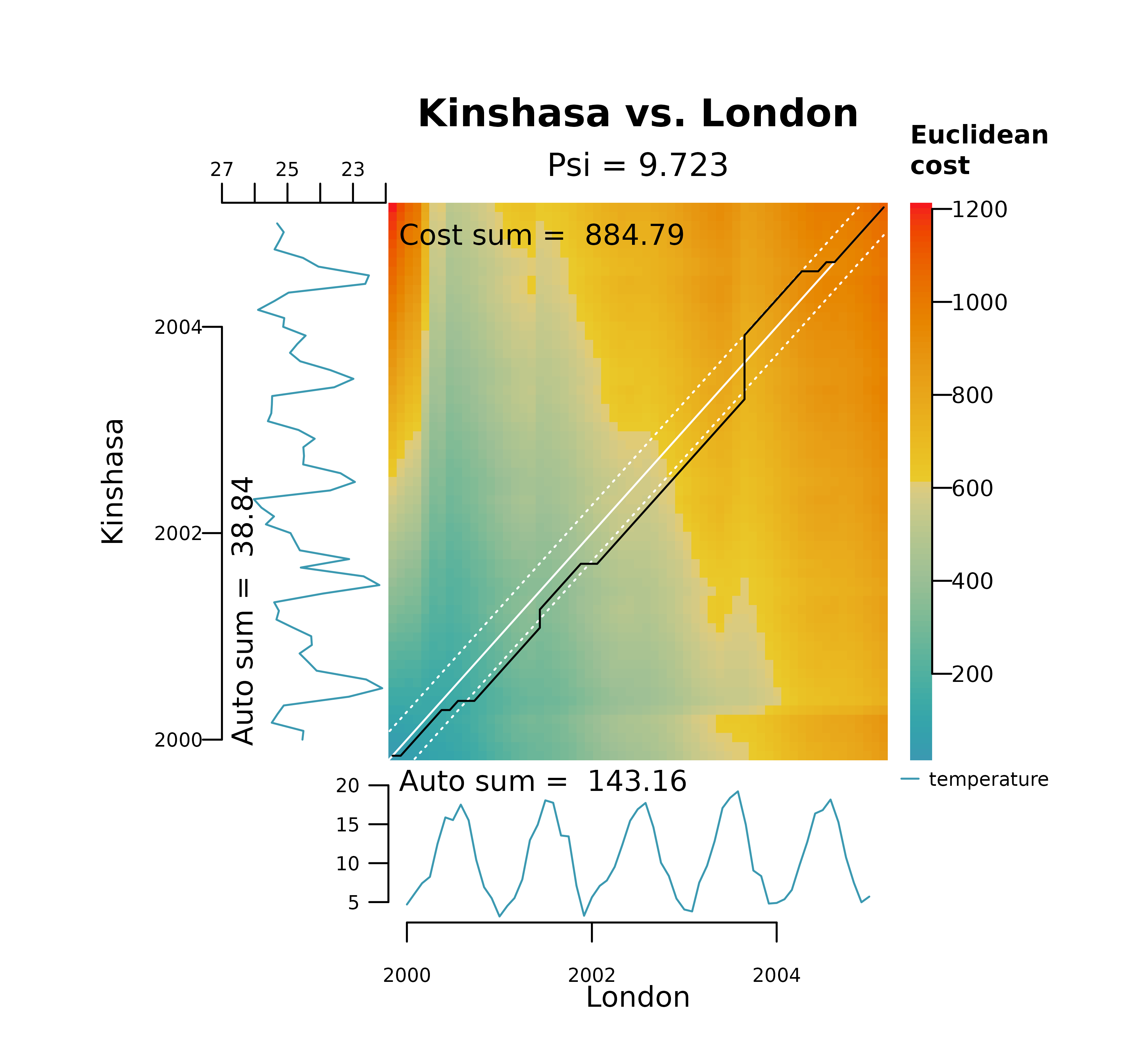

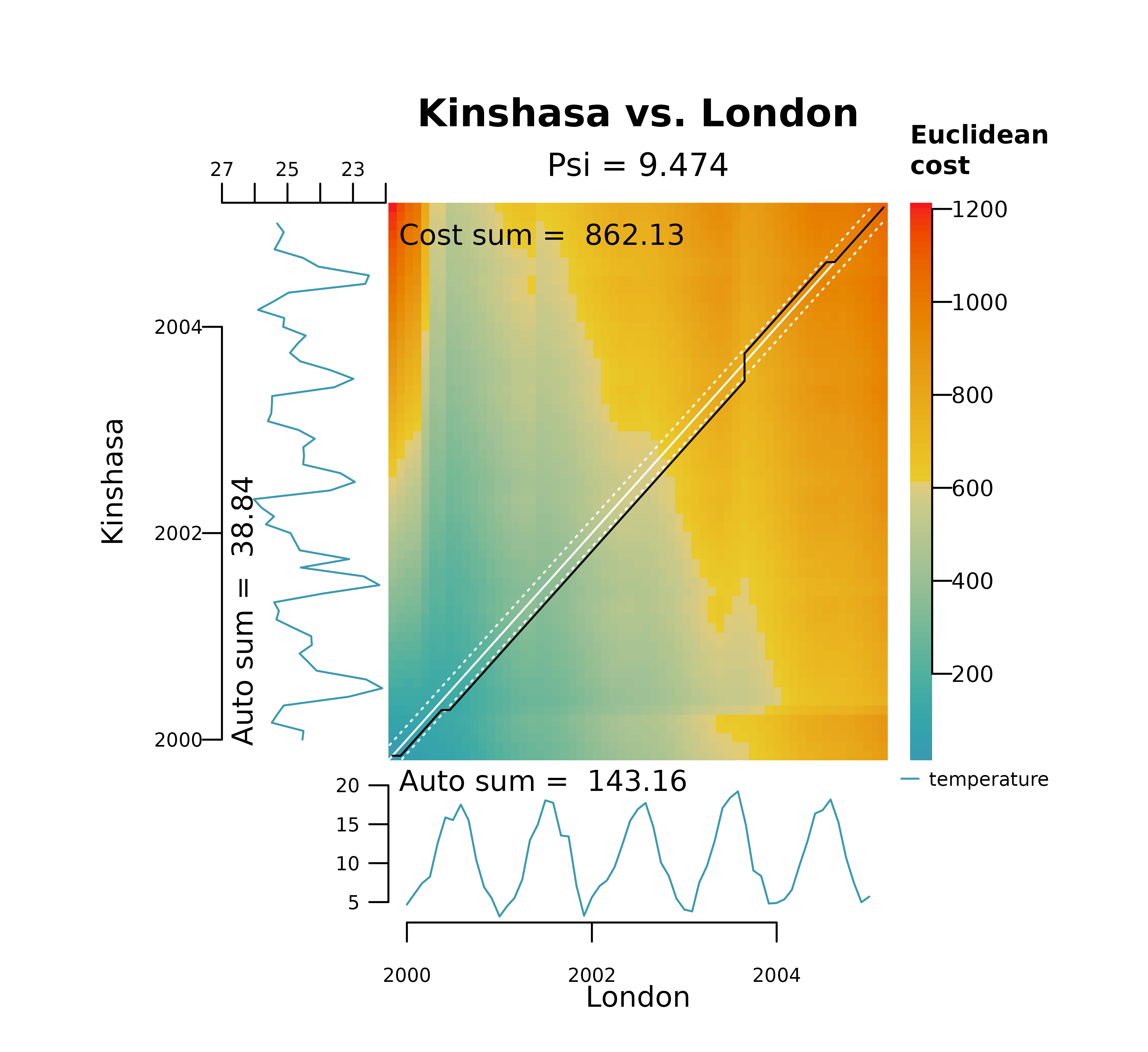

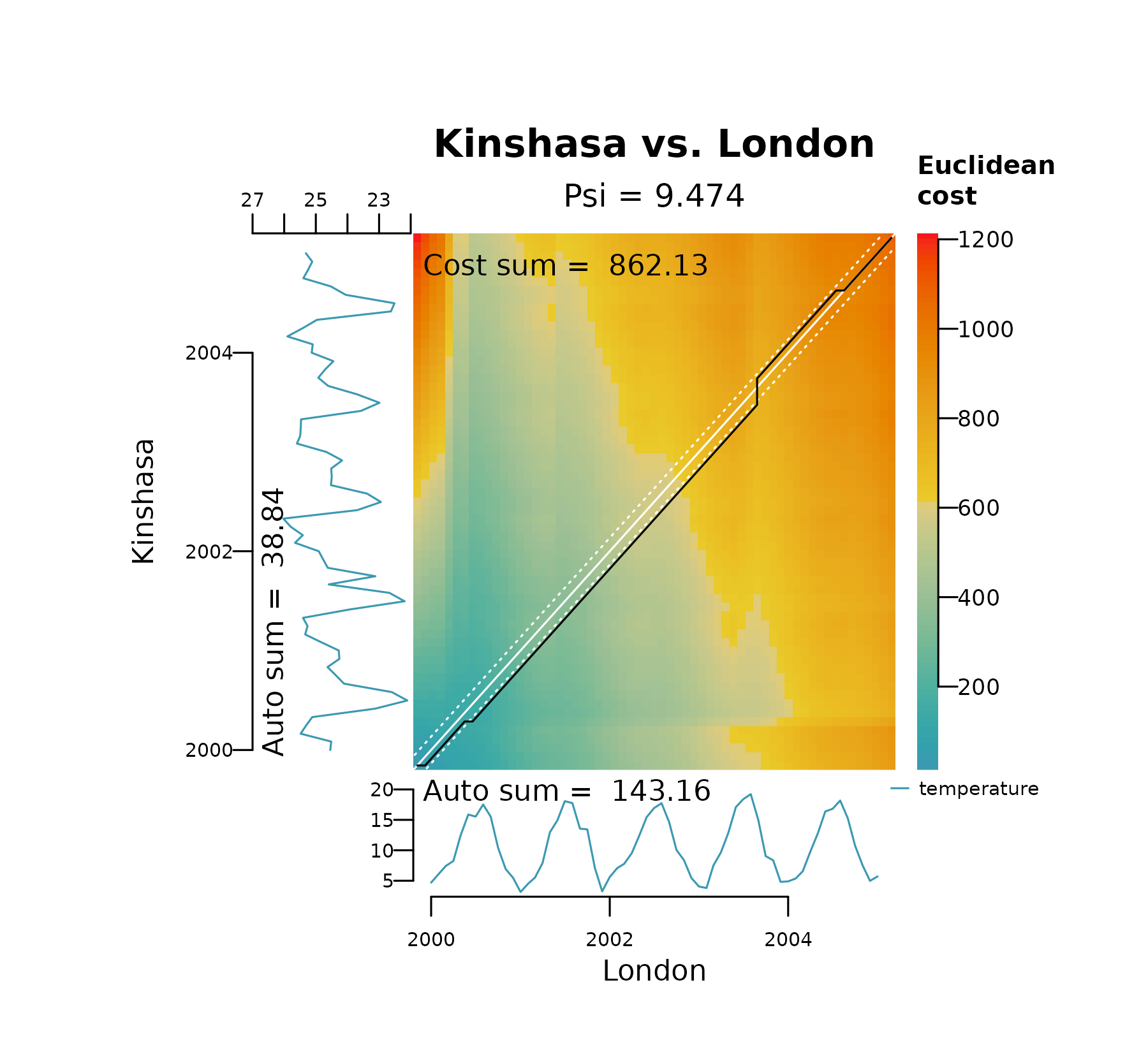

Constrained DTW

The function distantia() implements Sakoe-Chiba

bands to restrict the flexibility of the warping path via the

bandwidth argument. This argument represents the fraction

of space at both sides of the least cost matrix diagonal allowed for

warping. The plots below show the effect of decreasing

bandwidth on the area covered by the Sakoe-Chiba bands

(shown as white dashed lines) and how it restricts spread of the

alignment between London and Kinshasa on their raw temperature

values.

distantia_dtw_plot(

tsl = tsl_raw[c("London", "Kinshasa")],

bandwidth = 0.2

)

distantia_dtw_plot(

tsl = tsl_raw[c("London", "Kinshasa")],

bandwidth = 0.1

)

distantia_dtw_plot(

tsl = tsl_raw[c("London", "Kinshasa")],

bandwidth = 0.05

)

distantia_dtw_plot(

tsl = tsl_raw[c("London", "Kinshasa")],

bandwidth = 0.025

)

Sakoe-Chiba bands cannot fix bad alignments (that’s what data scaling is for), but can help diagnose them, given a tolerance level.

The code below runs distantia() for the raw temperature

data with two bandwidths: 1 for unrestricted dynamic time warping, and

0.25 as reference level.

df <- distantia(

tsl = tsl_raw,

bandwidth = c(1, 0.25)

)

df[, c("x", "y", "psi", "bandwidth")]

#> x y psi bandwidth

#> 1 London Paris 0.4241914 1.00

#> 4 London Paris 0.4241914 0.25

#> 3 Paris Kinshasa 7.3672711 1.00

#> 6 Paris Kinshasa 7.6432712 0.25

#> 5 London Kinshasa 10.2494423 0.25

#> 2 London Kinshasa 10.7561509 1.00Now, we can compute the psi differences across bandwidths for each pair of time series

df |>

dplyr::group_by(

x, y

) |>

dplyr::summarise(

psi_diff = diff(psi)

)

#> `summarise()` has grouped output by 'x'. You can override using the `.groups`

#> argument.

#> # A tibble: 3 × 3

#> # Groups: x [2]

#> x y psi_diff

#> <chr> <chr> <dbl>

#> 1 London Kinshasa 0.507

#> 2 London Paris 0

#> 3 Paris Kinshasa 0.276All pairs of time series with a psi_diff higher than

zero show warping paths that go beyond the 0.25 bandwidth.

Comparing DTW and LS

Dynamic Time Warping (DTW) and Lock-Step (LS) methods differ in scope and application.

DTW is ideal for comparing data that may be shifted in time due to positional differences, such as phenological time series observed across different hemispheres or elevations. It also facilitates the comparison of time series with varying lengths, observation periods, or sampling resolutions. This versatility makes DTW a general-purpose tool for time series analysis.

In contrast, LS is designed for synchronized time series that, at a minimum, must have the same length. While its scope is narrower, LS is more intuitive and accurate than DTW for comparing time series without time shifts, as it measures raw differences directly.

In essence, DTW, with its ability to adjust the time axis, answers the question, How similar can these two time series be?, while LS addresses the question, “How different are these two time series?”

The code below computes the dissimilarity score of the temperatures in Paris, London, and Kinshasa using DTW and LS and compares them in a data frame.

df_dtw <- distantia(

tsl = tsl_scaled

)

df_ls <- distantia(

tsl = tsl_scaled,

lock_step = TRUE

)

data.frame(

x = df_dtw$x,

y = df_dtw$y,

psi_dtw = round(df_dtw$psi, 3),

psi_ls = round(df_ls$psi, 3)

)

#> x y psi_dtw psi_ls

#> 1 London Paris 0.218 0.230

#> 2 London Kinshasa 1.052 2.705

#> 3 Paris Kinshasa 1.105 2.791For London and Paris, both DTW and LS show very similar values, because the time series are very similar and DTW cannot do much else to adjust them even more. On the other hand, DTW shows much lower values than LS when Kinshasa comes into play, as it compensates the seasonal shifts in these time series. In that sense, LS provides a more accurate image of the raw differences between these time series.

As a clear advantage, LS does not require data normalization for univariate time series, and therefore can provide a dissimilarity score in the same units of the variable at hand.

df_ls <- distantia(

tsl = tsl_raw,

lock_step = TRUE

)

df_ls[, c("x", "y", "psi")]

#> x y psi

#> 1 London Paris 0.4879081

#> 3 Paris Kinshasa 7.5416106

#> 2 London Kinshasa 9.3361647Comparing the dissimilarity scores above with the mean temperatures of the three cities below can give a sense of how approximate LS scores are to what we could expect.

Closing Thoughts

The distantia package strikes a balance between

flexibility and simplicity, enabling a more nuanced exploration of time

series data. With support for both dynamic time warping and lock-step

methods, it provides users with the tools needed to uncover insights

while respecting the unique constraints of their data. Whether you’re

working on sequence alignment or strict temporal comparisons,

distantia is designed to adapt to your analytical

needs.

I encourage you to give it a try and see how it fits into your workflows.